Practical Tips for Promotion

Sponsored by the Faculty Development Committee

Mentorship Program

|

|

Submitted by: David A. Young, MD, MEd, MBA, FASA

(Professor of Anesthesiology and the Huffington Department of Education, Innovation, and Technology and Vice-Chair Faculty Development)

The SEA Mentorship Program is an experienced group of SEA educational leaders willing to serve as mentors to faculty SEA Members.

The SEA Mentorship website has detailed information regarding the mentorship program, applications process, as well as mentor profiles.

If you are considering the use of mentorship for your faculty development, please consider the SEA Mentorship Program.

|

The "NO" Committee

|

|

Submitted by: Leila Zuo, MD (Associate Residency Program Director, Resident Learning, Assistant Professor, Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University)

Are you striving for improved work-life balance? Are you receiving constant requests for your time and energy at work, unsure if the project will be a value-add to the promotion process, or just take up crucial time you need to achieve your goals? Enter, the “No committee.”

As an academic physician, it is difficult to say “No” to new requests of your time, for many reasons. Often, there is more work, even interesting work, than there is staff to perform it. You may feel guilty saying no, or wish to impress your mentors/colleagues, or feel concerned saying no now will limit your approachability for future projects.However, being able to determine what projects are important for meeting your career goals, versus projects that are a time-sink and will leave you with less time and energy to pursue meaningful work, is critical. Assembling a “No Committee" can help provide clarity and help you manage your workload on the path to promotion.

The “No Committee” is made up of trusted friends, colleagues, and/or mentors who care about you, who understand your current responsibilities, and your future goals. They can provide a more objective eye than just your own. Any new opportunity or request of your time should immediately be directed to your “No Committee.” Send your “No Committee” an email that lists the opportunity and pros/cons about accepting the opportunity. Listen to their advice.There must be a group consensus to say “yes” for you to take on the opportunity. Additionally, the “No Committee” can help you craft a professional “no response” to the request.

|

COLLABORATION

|

|

Submitted by: Shamanatha Reddy, MD (Assistant Professor, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY)

There will be many of your colleagues working towards promotion also. Work together with them. It is not a race against each other. It is a team work. Work together on publications, put together a panel for a meeting, collaborate on a joint Grand rounds with another service. Collaboration may make the journey shorter and less painful. This process is like candle light. Use your candle to light someone else’s candle it doesn’t in any way make yours darker. It will brighten the environment.

|

Hold a Weekly or Monthly Meeting with Yourself

|

|

Submitted by: Rachel Moquin, EdD, MA (Assistant Professor, Director of Learning and Development, Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis)

Updating necessary documents for promotion can be a time-consuming and difficult task. This becomes even more challenging if we are catching up on weeks or even months of items to include in our CVs, dossiers, portfolios, etc. One strategy to consider staying on top of documentation and record-keeping is a weekly or monthly meeting with none other than yourself!

Select one day a week/month to schedule a block of time on your calendar. Try to be consistent about what day/time you choose to help this become routine. Focus on using this time for reviewing your calendar and work to identify items that should be added to your CV or promotion materials, as well as reflecting on what you need to roll ahead and prioritize in upcoming weeks.

During the meeting with yourself, sit down for 30-60 minutes to review the previous week, add any items to ongoing documents, give a final glance over weekly to-do lists and calendar items, and look into the week ahead to ensure preparedness for upcoming meetings and events. Aside from the key benefit of ensuring promotion materials are up-to-date and nothing gets forgotten, this time also allows for refocusing on priorities and goals, reflecting on progress with major projects, and catching up on organization.

References:

- Heyck-Merlin, M. (2012). The Together Teacher. Jossey-Bass.

|

Covey’s Time Management Matrix

|

|

Submitted by: Leila Zuo, MD (Associate Residency Program Director, Resident Learning, Assistant Professor, Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University)

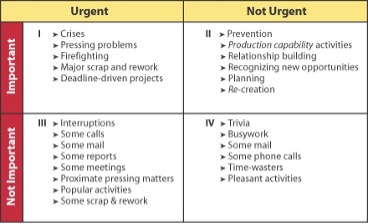

Promotion is comprehensive process that takes considerable time and effort to achieve. Academic faculty members face relentless pressures to generate revenue via the clinical mission, all while providing up-to-date evidence-based education to our learners, and contributing to advancing our specialty with scholarly work. Given that our time is a valuable and limited resource, skills in time management are vital to the success of academic physicians. A simple tool to manage your day-to-day workflow is Covey’s time management matrix. It can help to prioritize tasks that need you to complete, placing these tasks in 4 quadrants based on urgency and importance.

Quadrant 1 includes tasks that are important and urgent that need to be handled immediately. Examples include answering urgent pages, checking in with a learner with a time-sensitive problem, or any other deadline-driven project. These are tasks to DO.

Quadrant 2 includes tasks that are important, but less urgent. Examples include keeping the intraoperative record up to date, strategic planning for your department, or building a relationship with your department chair. These are tasks to PLAN, and often have a greater return on time and energy investment.

Quadrant 3 includes tasks that are less important, but urgent. Examples include answering some day-of-surgery questions from patients, responding to other people’s minor issues, and attending some meetings. These are tasks to DELEGATE if possible, or minimize.

Quadrant 4 includes tasks that are less important and less urgent. Examples include answering personal emails, scrolling through social media, or other distractions. These are tasks to ELIMINATE if possible, or minimize.

Steps to use the matrix:

- List all tasks you need to complete, including deadlines

- Identify the most urgent tasks, based on deadlines

- Organize tasks by importance

- Place tasks in the correct quadrant

- Assess your productivity

- Repeat regularly

References:

- Covey F. Habit-3. FranklinCovey. https://www.franklincovey.com/habit-3/. Published April 22, 2022. Accessed July 22, 2022.

- Gousset D. Stephen Covey's Time Management Matrix. Human Skills. https://humanskills.blog/time-management-matrix/. Published May 31, 2022. Accessed July 22, 2022.

- Murphy M, Pahwa A, Dietrick B, Shilkofski N, Blatt C. Time Management and Task Prioritization Curriculum for Pediatric and Internal Medicine Subinternship Students. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11221. Published 2022 Feb 22. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11221

|

Giving Yourself Grace

|

|

Submitted by: Veronica Carullo, MD, FASA, FAAP (Director, Pediatric Pain Management, Associate Professor of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS)

In 2015, at my annual review meeting, my Chair encouraged me to seriously consider submitting my CV for consideration for promotion from Assistant Professor to Associate Professor. I was intentionally and steadily working towards this goal as part of my 5-year professional development plan when I joined the faculty in 2011. In my first three years, I immersed myself in my clinical work, a combination of anesthesiology and pediatric pain medicine, and education. As the only pediatric pain specialist, I was afforded many opportunities to develop curriculum and participate in hospital committees and quality initiatives. In 2014, I was encouraged by my division chief to attend the medical school’s “Moving Up” faculty development seminar which demystified the promotions process and clearly delineated the various tracks for the institution’s promotions process. What I discovered was that I met and exceeded the criteria for the education and clinical legs, but was deficient in research and peer-reviewed publications. I was determined to meet my five-year goal of being promoted to Associate Professor I had set for myself, so in addition to my clinical responsibilities, I took on as many writing opportunities and became engaged in several research projects. What I didn’t take into consideration was the impact that this would have on my desires to fulfill my personal identity as a wife and mother of two young boys and on my well-being and self-care. I thought I could do it all and do it all well. I said “yes” to everything without any consideration for my self-care and well-being needs (exercise, sleep, being fully present to my family when I was home). Ultimately, I succeeded in meeting my five-year goal and in June 2016 received my academic promotion to Associate Professor. What I didn’t realize was that I was choosing the stress path and was well on my way to burnout.

As a young women professional, I felt fortunate to be surrounded by many strong women physician role models, mentors and sponsors who were invested in me. I felt inspired and empowered by them to help move forward gender equity. I felt a responsibility to be a strong role model to the talented young women and men that I mentored and sponsored. My “all or nothing thinking” defined success as “Associate Professor in 5 years.” I succeeded in improving the statistics for women, but in retrospect realize that in the process I was modeling behaviors that lead to burnout – behaviors such as saying “yes” to everything and in turn taking on more than plate could carry, making myself available 24/7 in the name of patient care, sleep deprivation, putting my own self-care needs at the bottom of my list of priorities.

Fortunately, along the way a fellow SEA colleague and mentor told me about Dr. Sasha Shillcutt’s Brave Enough® community. I read Dr. Shillcutt’s book, “Between Grit and Grace” and recognized the stress path I had unintentionally chosen for myself and made a decision to change paths towards a growth path. I made an investment in myself and signed up for Dr. Shillcutt’s 12-week “Brave Balance” journey. I was challenged to define my “why” and recognize some personal and societal barriers I would need to overcome to stay on my growth path. Most importantly, I learned that I am much more empowered than I ever thought. I am grateful for this community of women that continues to empower me daily to consider my personal and professional dreams and goals and to make decisions and set boundaries that honor that vision.

In 2016, I set a five-year goal of academic promotion to Professor. Fortunately, this time around I recognized that failing forward was more important than meeting my five-year goal. I want to challenge leaders in our specialty to think about whether we are creating an environment that honors the growth path and well-being for a diverse community. If not, what changes can we make in our processes in our institutions that will put us on this growth path?

And finally, a few parting thoughts for the younger generation of medical educators:

- Don’t let anyone define your “success story.” Only you know what that means for you!

- Turn your own internal criticism into a positive voice through self-compassion and affirmations.

- Fail forward by focusing on the process, not the outcome. Great processes will yield great outcomes.

- Learn how to recognize high levels of stress and respond with self-care.

- Build a network of mentors, sponsors, and colleagues who value your whole person and encourage you to set boundaries that promote your well-being.

|

MAKE ACADEMIC CONNECTIONS OUTSIDE YOUR DEPARTMENT BUT WITHIN YOUR INSTITUTION.

|

|

Submitted by: Gary E. Loyd MD, MMM (Director Perioperative Surgical Home, Henry Ford Health System, Clinical Professor, Wayne State University)

Make academic connections outside your department but within your institution. People have to know who you are.

|

GET A COPY OF THE PROMOTION AND TENURE POLICY MANUAL OF YOUR INSTITUTION

|

|

Submitted by: Michael Lewis MD (Professor and Chairman, Henry Ford Anesthesia Department)

- Know when you become eligible for the application for promotion/tenure and what the criteria are.

- Understand the promotion process. Take the time to read and understand the faculty handbook's description of the criteria for academic promotion. Somewhere in the bowels of your institutions published documents there will be a dull and lengthy document setting how the process, criteria and timelines for academic promotion.

- Create a checklist based on the described criteria. Demonstrate leadership and achievement in a range of fields such as teaching, research, and university governance.

- Secure support both internal and external support for your application. Letters will be sought to support your application.

- Chat with those who have been through the process. You can garner invaluable tips.

|

WORK ON BUILDING AND/OR MAINTAINING A RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR CHAIR THROUGHOUT YOUR CAREER

|

|

Submitted by: Issac Chu MD (Assistant Clinical Professor)

Often when academic anesthesiologists start their careers, they are simply trying to learn how to manage their clinical and academic work while staying under the radar. This usually means that they only speak to the Chair when they have a request, or worse, need to be reprimanded. This relationship makes it extremely difficult for a Chair to support that faculty member, since there is no basis for a positive relationship. It is difficult to succeed in a department without knowing the Chair's expectations. I recommend scheduling meetings with the Chair and/or discuss casually new project ideas so that the Chair may give the faculty member input and build a collaborative relationship.

|

JOIN A HOSPITAL COMMITTEE

|

|

Submitted by: Michal Gajewski DO (Assistant Professor)

This allows you to get involved in hospital policy making and it introduces you to other likeminded individuals. The added benefit is that you will meet faculty outside of your own department which could give you a different perspective on several issues. This then allows you to bring some of those views back to your department to implement change. Most importantly it lets your Chair know that you want to play a more prominent role and that you are motivated.

|

LEARN THE PROCESS FOR YOUR INSTITUTION

|

|

Submitted by: David Young MD, MEd, MBA, FASA (Full Professor)

Every institution has a specific process and policy for academic advancement and may greatly differ among institutions.

Early in your promotion process, identify the relevant details for YOUR institution to help plan your career trajectory effectively.

The relevant promotion details will likely address topics such as:

- Recommended timeline

- Curriculum vitae format

- Publication requirements [if any]

- Reference letter requirements

- Items valued in the promotion criteria [as well as items not highly valued]

- Process for promotion

- Requirement for departmental internal promotions committee approval [if any]

- Service requirements to the institution [if any]

|

EXTERNAL LETTERS – HOW TO GET THEM!

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, FASA (Full Professor)

You most probably will have to get letters of recommendation from faculty outside your institution. These letters should be written by someone who is familiar with your work. This can be a daunting task for junior faculty –it certainly was for me! Approach it strategically and start early!

- Your local state anesthesia society can be a gold mine – give a lecture for one of the meetings.

- Join the society of a subspecialty or a niche in anesthesia that you are interested in. Often times these societies are significantly smaller and more intimate than the larger societies. It may be easier to become involved and get to know people.

- If you have colleagues at other institutions, try to give Grand Rounds at these outside institutions.

- Get to know one or two medical students well – mentor them in producing a poster or an abstract.

- Try to collaborate on a project with a colleague in another institution or another service. An example of this is writing a book chapter with colleague in another institution – it does not have to be an anesthesia colleague – it could be a surgeon.

Think creatively!

|

JUST SAY NO !

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, CBA, FASA (Professor Anesthesiology, Montefiore Medical Center)

|

HOW TO PUBLISH A PEER REVIEWED PUBLICATION

|

|

Submitted by: Sheldon Goldstein MD (Associate Professor Anesthesiology Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Attending Montefiore Medical Center)

Peer-reviewed publications are important to substantiate your academic credentials. Tips to achieve publication success are provided below.

- Journals seek patient, laboratory and education research, review articles, and special articles. Each journal’s Guide for Authors will indicate the types of articles they consider.

- If you plan to perform a study, begin by performing a thorough literature search. If someone has published similar work, it may guide your study design, as you may appreciate ways to improve upon prior methods. Replicating results of a prior study is an important part of the scientific method. Still, if there are many related prior studies, performing a meta-analysis rather than a clinical study might be advisable.

- Higher quality research is more likely to be accepted, so plan the study carefully. Study design, data to be collected, and statistical analyses should be finalized in consultation with a statistician. A power analysis should be performed to determine the number of subjects required to answer the question.

- Write the Institutional Review Board (IRB) application as if it is a manuscript, including references. Then simply “drop results, table and figures” into the IRB, and finalize the discussion based upon results. You could even write part of the discussion before results return, based on what it known about the subject to date. That is, use the IRB application as a template for your manuscript.

- Well-graphed data may help you appreciate strength of results, note unexpected relationships and determine post-hoc analyses to perform. Therefore, graph the data before you write.

- Select a journal that fulfills your medical school’s promotion criteria. For example, they may require articles to be PubMed referenced. Do not waste time submitting to any journal if publication will not count towards promotion.

- Lesser quality journals will reach out to you via email. Most are open access, and require a fee. Neither is necessarily bad. What matters is whether the journal fulfills criteria for promotion at your institution. Case Reports in Anesthesiology is open-access and charges $500 per case report, but is PubMed referenced and may be worth the cost to you if you get your case report published and move on to your next publication.

- Follow the Guide for Authors carefully, as even a minor violation will result in the article being returned, and delay the review process.

- You may submit your manuscript to several journals before receiving an acceptance, so you might consider beginning with a prestigious journal, which will have more experienced editors. Even if your article is rejected, comments from editors at a more prestigious journal will help you improve your manuscript and facilitate acceptance at another journal.

- The review process is not a judgment that must be accepted, but a living conversation. I have personal experience with two publications that were rejected and felt strongly that both should have been accepted. I asked that both be reconsidered. The case report was subsequently accepted with minor revisions. The research paper was accepted without any substantial edits, and this in a well-regarded anesthesia journal. Editors are human, and sometimes make mistakes. If you feel your work is of high quality, do not give up.

|

BUILD YOUR PROFESSIONAL NETWORK

|

|

Submitted by: Titilopemi Aina, MD, MPH, FAAP, FASA (Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine)

|

MAXIMIZE YOUR CV BEING PROPERLY VALUED BY ALL REVIEWERS

|

|

Submitted by: David Young MD, MEd, MBA, FASA (Professor of Anesthesiology, Baylor College of Medicine)

|

MAXIMIZE YOUR SCHOLARLY ACTIVITY

|

|

Submitted by: Melissa Ehlers, MD (Professor of Anesthesiology, Albany Medical Center)

|

REVERSE MENTORING OR SHADOW MENTORING AS A TOOL IN PROMOTION

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, CBA, FASA (Professor Anesthesiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center)

|

IT’S ABOUT QUALITY

|

|

Submitted by: Deepika (Naina) Rao, MD (Associate Program Director, Pediatric Anesthesia Fellowship, Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatric Anesthesiology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital)

|

MOVING MOUNTAINS

|

|

Submitted by: Marina Moguilevitch, MD, FASA (Associate Professor Anesthesiology, Director Transplant Anesthesia, Montefiore Medical Center)

My road to promotion can serve as a perfect example how not to do it. The first eight years that I spent in my academic institution, I concentrated solely on clinical work. I mastered my clinical skills and achieved comfort with many technical procedures. I never presented outside my department, and never produced any scholarly activity. It was not the culture of my department at that time. No one encouraged me to engage in scholarly activity, and no one ever told me that it was an expectation in an academic institution.

The situation changed when a new chairperson came on board, and academic work and eventual promotion became a requirement. I urgently needed to organize myself to work on all the requirements- it felt like moving mountains. I received an immense amount of help, and encouragement from colleagues in my department. In four years, I managed to accomplish what I had not in the prior eight years.

The lessons I learned from this process:

- Start early

- Get organized

- Solicit as much help as possible from the people who have done it before

- Find courses in your institution which help you with targeted approach

- Get a mentor who can help and support you along the way

- Never got discouraged if your first attempt was not successful

|

DEVELOP YOUR PUBLIC SPEAKING SKILLS

|

|

Submitted by: Titilopemi Aina, MD, MPH, FAAP, FASA (Assistant Professor, Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine)

There are specific skills that were not taught in medical school, residency, or fellowship, but are expected in successful clinician-educators, such as public speaking. Physicians commonly give oral presentations in many venues – locally, regionally, nationally, and internationally. Toastmasters International offers an effective way to build your public speaking skills.

Since 1924, Toastmasters International has helped people build confidence as speakers and leaders. Toastmasters International is a nonprofit educational organization that offers a proven education program that helps improve communication and build leadership skills through a worldwide network of clubs. The organization’s membership exceeds 358,000 in more than 16,800 clubs in 143 countries.

The Toastmasters club experience offers a hands-on learning environment. Members give prepared and impromptu speeches, have opportunities to lead at every meeting and receive speech feedback and evaluations in a supportive environment. Also, compared to other public-speaking conferences and seminars, Toastmasters offers an ongoing and cost-effective program.

After every prepared speech given in Toastmasters, the evaluation focuses on vocal clarity and variety, eye contact, gestures, audience awareness, comfort level, and audience interest. My personal Toastmasters’ experience has allowed me to grow into an adept speaker. About a year ago, after giving a presentation as a Visiting Professor, I received overwhelmingly positive feedback about the content and delivery. I was immediately recommended as a speaker to another department within that same institution. By investing the time to develop my public speaking skills, I have opened the doors to invaluable opportunities in my pathway to promotion.

Are you ready to practice public speaking, improve your communication, and build leadership skills? Visit a club today! http://www.toastmasters.org/find-a-club

|

DOCUMENT, DOCUMENT, DOCUMENT

|

|

Submitted by: Zulfiqar Ahmed, MD, FAAP (Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, Wayne State University Anesthesia Residency Program)

During one’s career, you may start in a private practice, or an academic career, and move on to different locations and responsibilities. Physicians with academic or advocacy interests may find opportunities along the way, and avail them as they become visible. If you have continued to take interest in teaching and professional activities, keep a record of ALL collaborative activities.

Private practice physicians may find themselves back in academic practices. If life’s path takes you back to teaching, then the documentation that you have done will make it easier to chronicle your accomplishments. These documentation efforts will be very helpful in updating and boosting your application for academic promotion.

Take home message - DOCUMENT EVERYTHING!!!!!!!!!!!!!

|

GET ADVICE DIRECTLY FROM THE SOURCE

|

| Work on Building and/or Maintaining a Relationship with Your Chair Throughout You Career

Submitted by: Isaac Chu, MD (Clinical Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology, Keck School of Medicine)

“If you're interested in a promotion try getting advice directly from the source, your chairman. Often the rapport that is built from asking for advice and acting on it will assist in building a relationship as well as objectively contributing to the department's specific need”.

Adam Grant, Professor of Organizational Psychology – Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

References

Schwantes, Marcel. “3 Things Wharton's Adam Grant Says You Should Do to Be Truly Successful.” Inc.com, Inc., 2 May 2018, https://www.inc.com/marcel-schwantes/3-things-whartons-adam-grant-says-you-should-do-to-be-truly-successful.html

|

POINTERS FOR YOUR CV!

|

|

Submitted by: L. Jane Easdown MDCM, MHPE (Professor of Anesthesiology, Program Director, Vanderbilt University Medical Center)

Each step in your academic career requires a strategy for success. As we have found through SEA faculty development workshops, every institution has similar but not identical guidelines for promotion on education tracks. Some are more rigorous than others but the items they look for are likely to be the same. Each step is distinctive and here are some pointers on what they might be looking for as they peruse your CV.

| Rank |

Teaching |

Leadership |

Scholarship |

| Assistant to Associate Professor. Demonstrate eagerness to accomplish – take on many challenges. |

Evidence- volume and quality in all settings – classroom, workshop, simulation-topic, time number, location. |

Roles such as Director, Medical School Advisor, CCC, Program Director. Membership on local, regional, national committees-what have you done in these organizations? This is where you get your letters of recommendation. |

Sharing with others- manuscripts, talks, curricula, presentations, posters, research grant applications. |

| Associate to Full Professor. Time to FOCUS, HIGHLIGHT and SHOWCASE. |

Time to assist others, faculty development, quality over quantity, maintain Teaching Portfolio with evidence of learner assessment. |

Recognition as national/international leader-look beyond your own institution-be more than a member of a committee-be a productive member. |

First or last author manuscripts, high impact journals, stay away from predatory journals, national/international speaking engagements, reviewing journals, active research with funding, mentorship of faculty and trainees. |

|

UTILIZE PEER EVALUATIONS OF YOUR TEACHING SKILLS TO IMPROVE AS WELL AS DOCUMENT YOUR PROGRESS AND PASSION IN MEDICAL EDUCATION

|

|

Submitted by: David Young MD, MEd, MBA, FASA (Professor, Baylor College of Medicine)

Peer Evaluations of Teaching Skills can be very useful in your professional development as well as academic advancement. Remember to check your own institution’s promotion policies to see if a formal peer evaluation is required or strongly suggested. Even optional peer evaluations can be very meaningful to the faculty member especially if performed by an individual trained in the process.

Most peer evaluations are designed to be a formative process in which a trained evaluator focuses on the actual delivery of an educational session; the evaluator minimizes critiquing the actual content present but targets the evaluation on the overall teaching performance.

Peer evaluations focus on the teacher’s ability within several capacities including:

- Time management

- Session organization

- Learner engagement

- Learner comfort

- Promotion of understanding

Meaningful peer evaluations will start with an observation of a teaching activity followed by a debriefing session. This session is designed to provide honest and constructive criticism using direct observations from the session. In addition, the evaluator should provide useful alternatives or strategies to mitigate all reported concerns.

Depending on the institution’s promotion policies, receiving a Peer Evaluation of your Teaching Skills can improve your future teaching performance which can result in documented higher learner evaluation scores, perhaps increased future presentation opportunities as well as demonstrate your positive attitude in improving your teaching performance.

The SEA has an established Peer Coaching Program. Additional information on the Program can be found at: https://www.seahq.org/page/PeerCoaching

|

CITATIONS IN COVID-19

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, CBA, FASA (Professor Anesthesiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center)

Many of us were accepted to speak at conferences this year. Many of us will not speak at these conferences because COVID-19 has resulted in the cancellation of many in-person meetings. How do we cite “lost” presentations on our CV? According to the American Psychological Association, (APA) citing your accepted manuscripts and presentations in your CV for meetings that were canceled or made virtual is totally acceptable– and here’s how to do it.

- If the conference is cancelled, list the citation on your CV in the usual manner for the work, and put “(Conference Canceled)” at the end of the citation.

- If the conference is changed to online only, list the citation as if it were an in-person conference– there is no difference in citations for virtual and in-person conferences.

- If the conference occurs in-person or virtually, and you cannot attend or your session was canceled, and you were the sole author– list the citation, and in brackets at the end of the citation, state your session was canceled. This indicates that the meeting occurred, but your session was canceled.

References

https://apastyle.apa.org/

|

BEWARE PREDATORY JOURNALS – PUBLISH WISELY!

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, CBA, FASA (Professor Anesthesiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center)

There is nothing like that feeling of accomplishment when you get that acceptance letter from a journal for a manuscript that you have labored over for months. Do not waste your hard work by publishing your manuscript in a predatory journal.

What is a predatory journal?

A journal of poor quality, that usually charges a publishing fee, without an adequate peer review process or editing services, whether open access or not.

How do I know a journal is credible?

- Where is the journal indexed? Is it included in major databases such as PubMed, PubMed Central, Cochrane, DOAJ, Scopus, Medline, Web of Science, amongst others

- How long has the journal been in business?

- Is it peer reviewed?

- What is its impact factor?

- Does the journal tout a quick turnaround time for publication?

- Research the editorial board.

- Read past issues of the journal – look for spelling and grammatical errors.

Is there a list of predatory journals?

For a list from 2017 and earlier you can look at Beall’s list at www.beallslist.net

After 2017 until the present are Cabell’s blacklist (subscription only) or www.predatortyjournals.com/journals/ are two of the sites available

Do not just work hard, work smart too!

References

https://www.rxcomms.com/blog/6-ways-spot-predatory-journal/

http://health.library.emory.edu/writing-publishing/quality-indicators/journal-credibility.html

|

MENTORING TIPS

|

|

Submitted by: Michael C. Lewis MD, FASA, Joseph L. Ponka Chair (Department of Anesthesiology, Pain Management, & Perioperative Medicine, Henry Ford Health System, Professor of Anesthesiology, Wayne State University)

One consistent piece of advice that you will receive as you start your journey on the academic promotion ladder is find a mentor. So, after searching for a while you've discovered the suitable mentor. Now what?

- Aims are imperative: If you jointly define detailed, reachable goals at the start of your affiliation, with a timeline, your mentor can help you stay on track at each meeting.

- Regular Consistent Meetings: Define at the outset how frequently, for how long, and how you want to meet.

- Set an agenda: Have an agenda ready before each meeting.

- Allow for feedback: It could be positive, but also negative. Be open to hearing tough feedback.

- Take notes as you're meeting so that you can follow up via email. That will help a busy mentor stay on track and know what to focus on with you over the course of your relationship.

- Decide on an end date. Based on how long those short-term goals will take to achieve, decide how long you want the mentorship relationship to last. A good rule of thumb is usually four to six months, with the option to keep meeting informally.

- This relationship is not a therapy session. Remember to make and keep boundaries. We are human, and often personal issues will come into play during your sessions, especially if you have a pre-existing relationship or are talking about work-life balance. It's okay to vent. But make sure not to monopolize the session with personal issues or make it only about venting.

- Finally, consider establishing a board of mentors. No one mentor can help you achieve all of your goals. Maybe one mentor can help you consider a path to leadership because they are a supervisor. Maybe another can help with technical skills specific to making a job change. Another mentor may be aware of your skill set and could turn into a sponsor down the line. There is no right or wrong number of mentors as you progress through your professional career. Even if a formal mentorship period ends, keep these mentors in your life and updated of your achievements and pitfalls. They can be a guide when you're unsure and will feel appreciated that they helped you get to the place you're at in your career. Win-win!

- Some mentorships will end, based on where each person is at in life. Don't feel guilty, but close the loop respectfully. And remember to take care of yourself, above all else. Good luck!

|

F.O.C.U.S.

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, CBA, FASA (Professor Anesthesiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center)

As your career advances, and you begin to think about promotion, start to develop an area of expertise that will be the cornerstone of who you are academically. What will you be known for in the field of Anesthesiology. Your teaching portfolio should support your “cornerstone’ – A FOCUS.

- F-Find your educational or clinical passion and develop it. If you love what you do, it becomes easier to accomplish it.

- O-Organize your scholarly activities so that they highlight and complement your chosen passion.

- C-Channel your energies into working smart – have a vetted plan – ask for guidance for those who have done this before.

- U-Understand that academic promotion is a process – it takes time, dedication and a strategic plan of action.

- S-Simplify your academic promotions process by starting a teaching portfolio at the beginning of your academic career- it is NEVER too early to start.

|

CREATE A PERSONAL STATEMENT

|

|

Submitted by: Sadiq Shaik, MD (Assistant Professor, University of Central Florida College of Medicine)

Applications for promotion involves creating a packet of documents outlining your contributions to the institution. It can sometimes be overwhelming and confusing for the promotions committee to sift through the documents and decide.

A personal statement will help highlight your achievements and contributions that meet the criteria for the promotion.

Example items may include:

- Research including Principal Investigator projects, collaborative work with various departments, grants and mentoring other projects.

- Teaching activities including curriculum development, preceptor-ships, regional/national committee work and educational grants.

- Presentations at national meetings and original findings that have led to changes in medical practice across the nation in the specialty area.

- Scholarship as evident by publication of manuscripts, peer reviewer of manuscripts, editorial work, book chapters, and book reviews.

- Clinical service experience including the number of years with examples of contributions to various departments, boards and institutions. Examples can include development of programs, policies and procedures that contributed to the scope and quality of practice.

In summary, the key elements to include:

- What do you do?

- How have you advanced academics?

- How will you contribute to the mission of the college of medicine?

|

THE MINI CEX

|

|

Submitted by: Scott D. Markowitz, MD (Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus)

- Simple and straightforward teaching and feedback tool employed for learners that can be meaningful and lasting contribution to your teaching portfolio.

Consider a “piece” of education, a procedure or a technique for trainees to master, and create a set of expectations and a scoring system around those expectations. The evaluation is a few key questions, which can be put on, for example, an index card (or a short email/online survey).

For example:

- PIV placement technique:

- Equipment ready

- Gloves on

- Tourniquet applied

- Area prepped

- Maintained sterile or no-touch technique from needle insertion through dressing application

- Confirmed flow and flush while checking for signs of abnormal placement

Each question could have a y/n/don’t know or a scale from excellent to unacceptable. After observing and completing the card, it could be used for feedback or collected for QI purposes.

- The mini CEX form would be submitted as a piece of scholarship (teaching or QI tool) that could be peer-reviewed by the clinical operations or education committee of your department, and could produce scholarship in the form of QI or research study component.

|

SPONSORSHIP AND MENTORSHIP – KNOW THE DIFFERENCE

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, CBA, FASA (Professor of Anesthesiology)

As you move along your trajectory of promotion, undoubtedly you will meet individuals that help you. Most are familiar with mentors, but are you familiar with sponsors, and do you know the difference?

- A Sponsor is an individual that sits in a position of power, who publicly advocates for you. They make the phone call, hire you, or make the position for you to be hired into .They recognize you as a “high potential.”

- A Mentor is an individual that advises you on your path. They write the letters of recommendation and wait for opportunities to arise. They recognize your ability to succeed.

Check out the table below for a snapshot of the differences. Both sponsors and mentors are valuable to your career, but knowing the difference may make your pathway a bit smoother.

| Sponsor |

Mentor |

Supporter |

| Hires you for a position |

Writes a LOR for a position |

Is happy when you receive the position |

| Is in a position of power to actively mention your name for a new role |

Writes a LOR for a new role |

Is happy when you receive the new role |

| Actively seeks out/ makes opportunities where you can advance |

Waits for opportunities to arise to write a LOR |

Is happy that you are advancing |

| Makes a phone call/ has a 1:1 with a decision maker who has the authority to say yes |

Writes a LOR and encourages you |

Prays for you |

| Tells you what you need to get the job specifically |

Will suggest leadership courses and coach you |

Encourages you to go after the position |

|

FOOD FOR THOUGHT – AN OUT OF THE BOX STRATEGY

|

|

Submitted by: Isaac Chu, MD (Assistant Professor of Clinical Anesthesiology, Keck School of Medicine)

In the business setting, it is common knowledge that increases in salaries and status are often associated with changing companies. This factor suggests that for an employee seeking a promotion, you may want to seriously consider outside opportunities as a way to ascend the academic ladder. Anecdotally, academic faculty have reported changes in title and/or salary as incentives offered to move to a new academic setting.

Keng, Cameron. “Employees Who Stay In Companies Longer Than Two Years Get Paid 50% Less.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 2 Jan. 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/cameronkeng/2014/06/22/employees-that-stay-in-companies-longer-than-2-years-get-paid-50-less/#7374f782e07f.

|

STEPS FOR SELF-PRESERVATION THROUGH THE PROMOTIONS PROCESS

|

|

Submitted by: Ingrid Fitz-James, MD (Assistant Professor, Montefiore Medical Center)

- Promoting Self

- Sustaining Self

- Enhancing Self

- Sustain Departmental and Others' Professional Interest in Your Subject of Choice by declaring Your Interest while remaining of service to others.

- Remain informed about "new knowledge" regarding your Subject of Choice.

- "Carve Out a Place for Yourself" - Identify a subject of interest to you and to others, to which they may not want to dedicate the effort or time to become fully informed.

- "Aspire to New Plateaus" - Carve out regular time allotment to this pursuit, to arrive at conclusions and observations that "Stand the Test of Time."

- Make the pursuit of your subject in parts and elements that can be woven in one single subject, "Don't get Boxed In," and weave together the multiple facets which you have pursued over time. "Reach Deep" across Multiple Disciplines to be informed about the Application of "new knowledge" to your Subject of Choice. "Listen to the Voice of the Wind." Explore the conclusions reached by other disciplines about the subject.

- Do not be like everyone else, develop your own style. "It's OK to be a Little of the Wall" but do not be “Off the Wall." Remain factual in content and accurately referenced with respect to your sources.

- Dedicate care to a few presentations in terms of depth so that evolution into a National Presentation is an attainable goal.

The italicized quotations, referenced with deference, originated from a circular of the Sierra Club, a steward of environmental protection, under the heading ”Advice from a CANYON;”

|

MAINTAIN A TEACHING PORTFOLIO IN CONJUNCTION WITH YOUR CV

|

|

Submitted by: Bryan Mahoney, MD (Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and West Hospitals)

For a physician educator, a teaching portfolio allows you to place your educational accomplishments in the best possible light.

Essential components of your teaching portfolio should include:

- A statement of your Educational Philosophy

- Clinician Educator portfolio:

- Educational Curricula Designed, Implemented, and Instructed (includes the program, audience, teaching site, duration, frequency, your role, and the overall planning time)

- Teaching Activity Report (a list of lectures, small groups, grand rounds, clinical teaching within your home institution and evaluations of these sessions)

- Educational Administration & Leadership (roles within your institution and program)

- National & International Scholarship in Education (a brief statement of your areas of educational expertise followed by invited lectures and presentations or talks at national and international conferences)

- Educational Materials with National & International Impact (materials you have created and shared organized in an appendix)

- Advising & Mentoring (a list of mentees with testimonials from mentees or evaluations of your teaching or mentoring)

- Honors & Awards in Education

If you have served in a significant education role (Program Director, Vice-Chair of Education), create an additional section cataloguing the accomplishments you achieved within that role.

Of course, if your institution already has a form for an Educational Portfolio, you will need to incorporate these elements to conform to the available template.

|

LETTERS FOR PROMOTION: THINK AHEAD, YOU WILL NEED THEM!

|

|

Submitted by: Jane Easdown, MDCM, MHPE (Professor of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University)

Look over your university policies for promotion to be sure you are in compliance with their instructions on this.

- These letters might be internal or external to your healthcare system

- These are individuals who know your work and can vouch for its quality and impact

- Most of us give letter writers that we know personally a “heads up” in advance to determine that they are prepared and also that they will indeed support you

Internal Letters:

- For clinical tracks, you will be asked to recommend colleagues from within your own healthcare system.

- Some of these might be from colleagues in your own department. They might be surgical or medical colleagues if they know your work and can report on your contribution and impact

- If you work with a nursing manager, administrator or QI committee then this might be an important person to add to the list

- You might be asked to provide letters from mentees, former residents or fellows

External Letters:

- Start thinking early in your career about what external organizations you might join and become active in

- The work that you do for SEA, SPA, SOAP, etc. will be not only be enjoyable and instructive to your career, but will also allow you to make the contacts necessary to get those important outside letters.

- Individuals that can write letters are committee chairs, board members, etc. They should know you because of your activity in meetings, on committees, article for newsletters, etc. Institutions often request that the letter writer not be a close collaborator. That might be a person you write articles with on a regular basis. Generally if you have done some work together, for example, a workshop one time, this is not a problem.

Follow-Up:

- When you have received your long awaited and deserved promotion (can take up to a year!) please remember to let your letter writers know since they will not be informed by the promotion committee. They will really want to know and celebrate your success!

|

ALL PUBLICATIONS ARE NOT EQUAL! KNOW THE HIERARCHY OF THE PUBLICATIONS IN YOUR INSTITUTION!

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, CBA, FASA (Professor of Anesthesiology)

- Do manuscripts have to be Pub Med cited?

- Is a manuscript weighted the same as book chapter? Or a case report?

- Does placement of my name on a publication matter?

- Are web based open access journals weighted the same as traditional journals?

- Should everything I publish be peer reviewed?

These are all questions that you should know the answers to when “writing for promotion.”

Remember work hard, but work smart!

|

DETERMINE YOUR TRUE REASON(S) FOR WANTING PROMOTION

|

|

Submitted by: David Young MD, MEd, MBA, FASA (Full Professor)

Ascertain your real purpose for wanting promotion. Once these reason(s) are determined, you can then make an educated decision on the time and effort required in order to complete this comprehensive process. Surprisingly, not all people inspiring academic promotion mostly want this only for the self-fulfilling aspects.

If one were to deeply consider their motives for wanting promotion, they may realize that the most important part of receiving promotion is NOT the actual promotion but the following:

- Financial benefits (i.e. pay raise)

- Institutional benefits (i.e. college reimbursement for associate professor and higher)

- Tenure (i.e. limited protection against termination)

- Leadership positions (i.e. Chief or Chair positions only given to advanced ranks)

- Future interests (i.e. more marketable if higher rank)

Many of these alternative reasons can also be obtained by other methods. In addition, many of these reasons are institutional dependent.

|

REVERSE MENTORING

|

|

Submitted by: Tracey Straker, MD, MS, MPH, CBA, FASA (Professor of Anesthesiology)

- Consider a “reverse mentoring“ situation.

- Reverse mentoring is a mentoring relationship based on reciprocity between a senior faculty and a junior faculty.

- The senior faculty may mentor you in navigating the promotional process, and you can reciprocate by mentoring the senior faculty in areas that may be deficient such as social media and technology.

|

BASIC FACTS

|

|

Submitted by: Michael C. Lewis, MD, FASA (Professor and Chairman, Henry Ford Anesthesia Department)

- Learn the Language: read and reread the rules for promotion at your home institution. Make a check list and timeline based on these rules.

- Create a Narrative: If you are applying for promotion from Associate to Professor you should be able to tell the story of your career. If your institution allows it, create a portfolio documenting your achievements. It should be accompanied by an Executive Summary.

- Make Sure that Folks on the Promotion Committee Know Who You Are. This simple exercise can be very helpful. When individuals have an ‘emotional’ attachment to a name (hopefully good) they may argue your case much more effectively.

- Be Nice to Administrators: They mediate all information flow in a University. Including everything concerned with advancement. They need your respect.

- Have a list of Potential References from outside institutions that you can provide to your chair.

|

UTILIZE THE BUSINESS FIELD

|

|

Submitted by: Isaac Chu, MD (Assistant Clinical Professor, Keck School of Medicine)

- Promotional opportunities and administrative responsibilities are an important part of any academic department.

- Few of us are well educated in the field of business, which has a tremendous amount of resources devoted to these topics.

- Adam Grant, a renowned professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, writes on topics involving collaboration, networking, and organization- all useful topics in the journey for academic promotion.

|

KEEP RECORDS

|

|

Submitted by: Regina Fragneto, MD (Professor of Anesthesiology, University of Kentucky College of Medicine)

Keep a record of every presentation, resident lecture and other academic activity as you actually do it. Trying to remember all your educational activities as you are putting together your teaching portfolio for promotion is painful!

|

|